Useful Formulas for Math

I am opening a new post for formulas in Learning Theory and general Machine Learning area. It is purely mathamatically based. It is suggested to use it as reference instead of studying them one by one.

Note: You can share this post to social network at the bottom.

Probability Theory and Expectation

Law of Total Expectection (a.k.a. Tower Rule)

Let random variable X and Y defined in the same probability space. Then, $E_X (X) = E_Y(E_X(X\lvert Y))$.

Proof:

\[\begin{align} E_Y (E_X (X\lvert Y)) &= E_Y(\sum_{x} x * P(X\lvert Y))\\ &= \sum_{y} \big[ \sum_{x} x* P(X=x\lvert Y)\big] P(y) \\ &=\sum_{x} \sum_{y} x* P(Y)* P(X=x\lvert Y)\\ &=\sum_{x} x* \sum_{y} P(Y)* P(X=x\lvert Y)\\ &=\sum_{x} x* \sum_{y} P(X,Y) \\ &=\sum_{x} x*P(x)\\ &=E_X (X) \end{align}\]Learning Theory

L’ Hospital Rule

L’ Hospital Rule uses derivatives to help evaluate limits involving inderterminate forms. It states that for functions $f$ and $g$ which are differentiable on an open interval $I$ except possibly at a point $c$ contained in $I$,if

\(\lim\limits_{x\to c} f(x) = \lim\limits_{x\to c} g(x) = 0\) or \(\pm \infty\)

$g^{\prime}(x)\neq 0$ for all $x$ in $I$ with $x\neq c$ and $\lim\limits_{x\to c} \frac{f^{\prime}(x)}{g^{\prime}(x)}$ exists,

then $\lim\limits_{x\to c} \frac{f(x)}{g(x)} = \lim\limits_{x\to c} \frac{f^{\prime}(x)}{g^{\prime}(x)}$

Markov Inequality

For a positive random variable $X \leq 0$,

\[Pr[X \geq b] \geq \frac{E[X]}{b}\]Prove: $E[X] = \sum_x xPr(X=x) \geq \sum_{x\leq b} bPr(X=x) = bPr(X\geq b)$

Math

Log properties

$a^{log_b n} = (b^{log_b a})^{log_b n} = (b^{log_b n})^{log_b a} = n^{log_b a} $

Geometric Series

$1 + x + x^2 + \dots + x^n = \frac{1-x^{n+1}}{1-x}$ for $x\neq 1$

$1 + x + x^2 +\dots = \frac{1}{1-x}$ for $\lvert x\rvert <1$

Harmonic Series

$\sum\limits_{i=1}^{n} \frac{1}{i} = \ln{n} + \gamma + \frac{1}{2n} - \frac{1}{12n^2}$ is the best approximation for the series.

Stirling’s approximation

\[\log_2 n! = n\log_2 n - (\log_2 e)n + \mathcal{O}(\log_2 n)\]Trace Properties

$tr(AB) = tr(BA)$

$tr(ABC) = tr(CAB) = tr(BCA)$ which is called cyclic property of trace.

$\nabla_{A} tr(AB) = b^{T}$

$\nabla_{A^T} f(A) = (\nabla_A f(A))^T$

$\nabla_A tr(ABA^TC) = CAB + C^TAB^T$

$\nabla_A \lvert A\rvert = \lvert A\rvert (A^{-1})^T$

Woodbury Matrix Identity

It says that for any given A with n by n and U with n by k and C with k by k and V with k by n such that A and C are nonsingular, we have :

\[(A + UCV)^{-1} = A{^-1} - A^{-1}U(C^{-1} + VA^{-1}U)^{-1}VA\]Proof can be found on Wiki easily.

Some useful approximations

-

$(1 - \frac{\lambda}{n})^n \approx e^{\lambda}$ where $\frac{\lambda}{n} < 1$

-

Binomial approximation: $(1+x)^{\alpha} \approx 1 + \alpha x$ when $\lvert x\rvert <1$ and $\lvert \alpha x\rvert \ll 1$.

-

Euler related: $\sum\limits_{n=1}^{\infty} n^{-2} = \frac{\pi^2}{6}$

Maclaurin series

-

$\ln(1-x) = -\sum\limits_{n=1}^{\infty} \frac{x^n}{n}$ when $\lvert x\rvert < 1$ or $x=-1$

-

$\ln(1+x) = -\sum\limits_{n=1}^{\infty} (-1)^{n+1} \frac{x^n}{n}$ when $\lvert x\rvert < 1$ or $x=1$

Vector Calculus

Gradient - Vector in, Scalar out

Let’s denote a function $f:\mathbb{R}^n\mapsto\mathbb{R}$. The gradient of the function is defined as:

\[\triangledown_x f = \frac{\partial}{\partial x}f = \begin{bmatrix} \frac{\partial f}{\partial x_1} \\ \frac{\partial f}{\partial x_2} \\ \vdots \\ \frac{\partial f}{\partial x_n} \end{bmatrix}\]It simply says that for a function which takes a vector as input and a scaler as output, the gradient of the function is a column vector which each element is the derivative of f with respect to a single component of x. The i-th element indicates how the change rate of function is with respect to i-th variable or i-th dimension.

For example, $y = x^Tz$ where $x \in \mathbb{R}^n$ should be a good practice to work on.

Jacobian Matrix - Vector in, Vector out

For Jacobian, the case is more complicated. Let’s denote a function $f:\mathbb{R}^n\mapsto\mathbb{R}^m$. The Jacobian of the function is defined as:

\[J_x(f) = \begin{bmatrix} \frac{\partial f_1}{\partial x_1} & \frac{\partial f_1}{\partial x_2} & \dots & \frac{\partial f_1}{\partial x_n}\\ \frac{\partial f_2}{\partial x_1} & \frac{\partial f_2}{\partial x_2} & \dots & \frac{\partial f_2}{\partial x_n} \\ \vdots & \vdots & \dots & \vdots \\ \frac{\partial f_m}{\partial x_1} & \frac{\partial f_m}{\partial x_2} & \dots & \frac{\partial f_m}{\partial x_n} \end{bmatrix}\]It says that if we have a function which takes a vector as input and putput a vector, the Jacobian of this function is a matrix described above. The $J_{i,j}$ says about how the change rate of i-th function is with respect to j-th variable.

For example, $f(x,y) = (x^2 + y, y^3)$ should a good one to try.

Generalized Jacobian Matrix - Tensor in, Tensor out

In previous Jacobian matrix, we assume the input is an vector and output is an vector too. However, we can generalize this to a tensor to form generalized Jacobian matrix.

Suppose that $f:\mathcal{R}^{N_1\times \dots\times N_{D_x}}\mapsto\mathcal{R}^{N_1\times \dots\times N_{D_y}}$. It means the input to f is a $D_x$-dimensional tensor of shape $N_1\times \dots\times N_{D_x}$ and the output of f is a $D_y$-dimensional tensor of shape $N_1\times \dots\times N_{D_y}$. Thus, the generalized Jacobian matrix has the shape of $(N_1\times \dots\times N_{D_y})\times(N_1\times \dots\times N_{D_x})$.

You can image this generalized Jacobian matrix as a “2D” matrix where the row dimension is indexed by $N_1\times \dots\times N_{D_y}$ and the column dimension is indexed by $N_1\times \dots\times N_{D_x}$.

Now, given that $i\in\mathcal{Z}^{D_y}$ and $j\in\mathcal{Z}^{D_x}$ We can have:

\[\bigg(\frac{\partial y}{\partial x}\bigg)\_{i,j} = \frac{\partial y_i}{\partial x_j}\]So we know that $y_i$ and $x_j$ are all scalars. Thus, $\frac{\partial y_i}{\partial x_j}$ is also a scalar. This tells us the relative rates of change between all elements of x and all elements in y.

Hessian Matrix - Vector in, Scalar out

Whereas gradient and Jacobian are somewhat like a first order derivative, Hessian is somewhat like second order partial derivative. Let’s denote a function $f:\mathbb{R}^n\mapsto\mathbb{R}$. The Hessian of the function is defined as:

\[H_x(f) = \begin{bmatrix} \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x_1^2} & \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x_1 \partial x_2} & \dots & \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x_1 \partial x_n}\\ \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x_2 \partial x_1} & \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x_2^2} & \dots & \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x_2 \partial x_n} \\ \vdots & \vdots & \dots &\vdots \\ \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x_n \partial x_1} & \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x_b \partial x_2} & \dots & \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x_n^2} \end{bmatrix}\]The $H_{i,j}$ indicates how the change rate of the function is with respect to i-th variable and j-th variable where i and j might be same.

For example, $f(x,y,z) = x^2 + y^2 + z^2$ could be an example for practice.

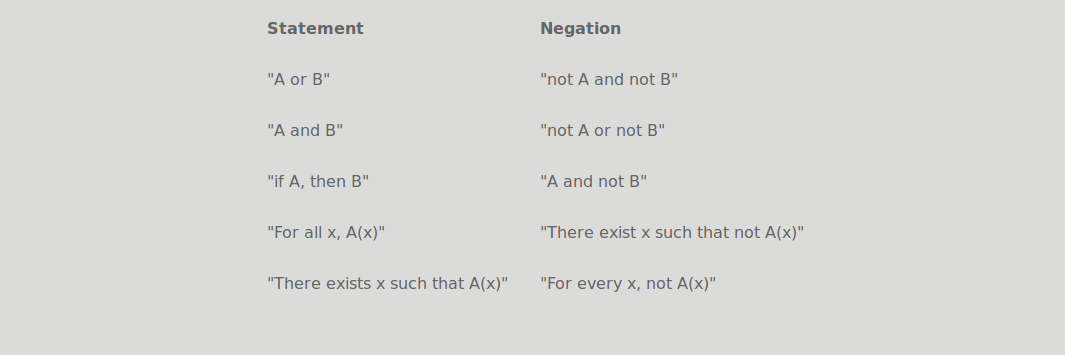

Negation of Logic Summary

Product of Sum

In general, we have:

\[(\sum\limits_{i=1}^n x_i)(\sum\limits_{j=1}^m y_j) = \sum\limits_{i,j}^{n,m} x_i y_j\]It cannot be reversed.